Arthur Stanley EddingtonArthur S. Eddington (1882–1944), astrophysicist, was an early supporter of Einstein’s theory of relativity. He became director of the Cambridge Observatory in 1914. In 1923 he published one of the first textbooks on the theory of relativity. Since Eddington seasoned many of his books with vivid examples and humorous anecdotes, his works on the philosophy of science were also read outside the scientific community. led the 1919 expedition to view the solar eclipse, which set out to confirm one of the predictions of Einstein’sAlbert Einstein (1879–1955) was one of the most important physicists in the history of science. He began developing the theory of relativity in 1905. In 1914 he joined the Prussian Academy of Sciences and in 1917 became director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, which had been founded for him as a means to support his work. He won the Nobel Prize in 1921 (awarded in 1922). He spent periods teaching and conducting research in the USA. In 1932/33 he went to Princeton, never to return to Germany. He was clearly opposed to Nazi Germany and did not renew his ties with the country, even after 1945. He retired in 1946 and continued his work as professor emeritus at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton. theory of relativity: namely, that large masses (in this case, the Sun) deflect light (in this case, from stars that are close to the Sun as seen from Earth).

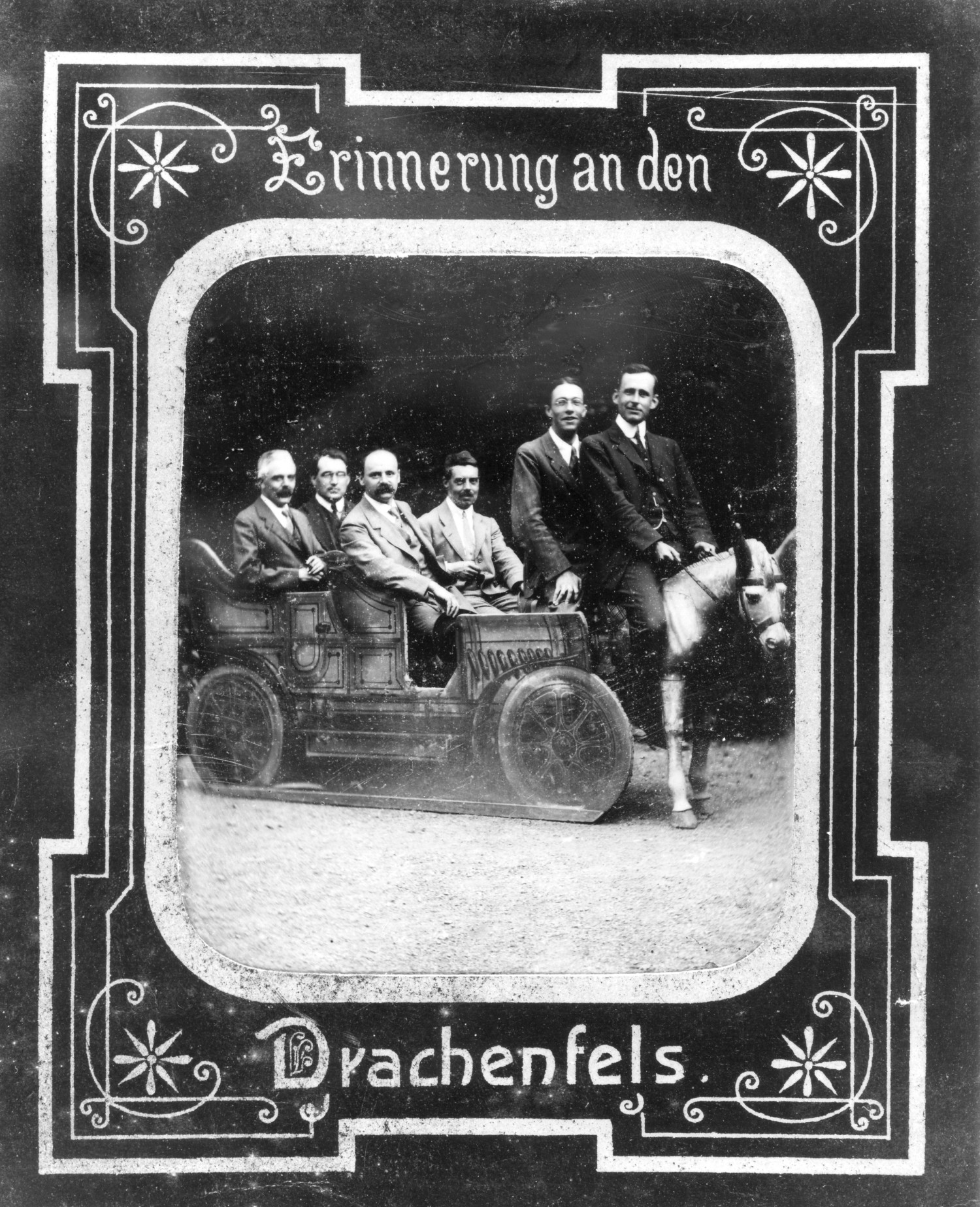

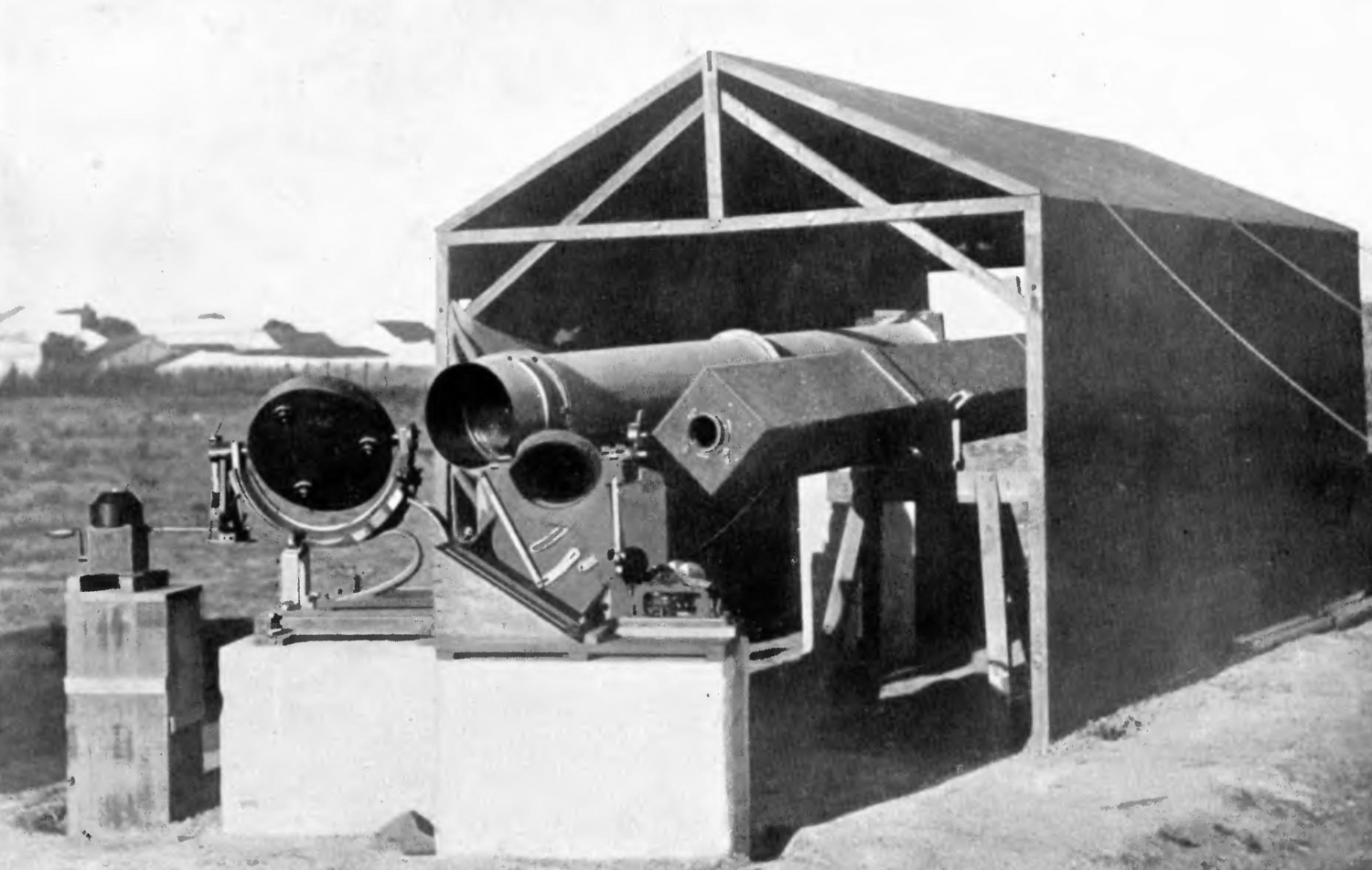

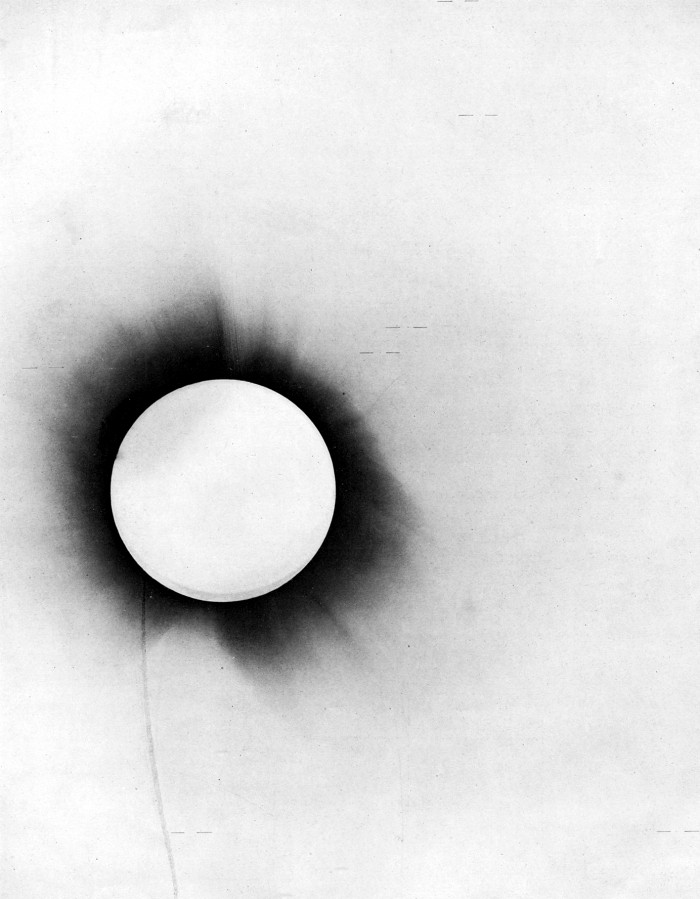

The aim of the expedition was to begin by photographing the star-studded night sky and then to take pictures of the same area of the sky when the Sun was eclipsed by the Moon – because during a solar eclipse, the stars can also be seen during the day. The expedition went to two destinations simultaneously: to the Brazilian village of Sobral in the state of Ceará and to the island of Príncipe (São Tomé and Príncipe, located off the coast of Equatorial Guinea and Gabon). Eddington himself was on Príncipe, where the weather was rainy and cloudy. Just before the eclipse, the skies cleared and his team managed to take at least two usable photos of the eclipse and of the area surrounding it. The Sobral team had more success and came away with eight photos. The team subsequently convened in England to analyse the pictures.

Eddington reported his preliminary results at a conference in early September 1919. A definitive detailed evaluation was presented by his colleague Andrew Crommelin at a joint meeting of the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society on 6 November 1919: the deflection of the starlight at the edge of the eclipsed Sun was 1.98 ± 0.18 arc seconds for one of the telescopes and 1.6 ± 0.31 arc seconds for the other. Einstein’s prediction was 1.75 arc seconds and, based on this, the results of the expedition were viewed as confirmation of the theory of relativity.

In 1979 Eddington’s photographic plates were checked again using modern measuring equipment, which yielded a result of 1.90 ± 0.11 arc seconds, meaning that the measurements taken at the time were fairly reliable. Final confirmation of the relativistic deflection of light only came in the 1980s, however, when it was verified using radio astronomy: the radio waves of two neighbouring stars were analysed as the Sun passed them, which allowed a relativistic change in their position to be determined with even greater accuracy.

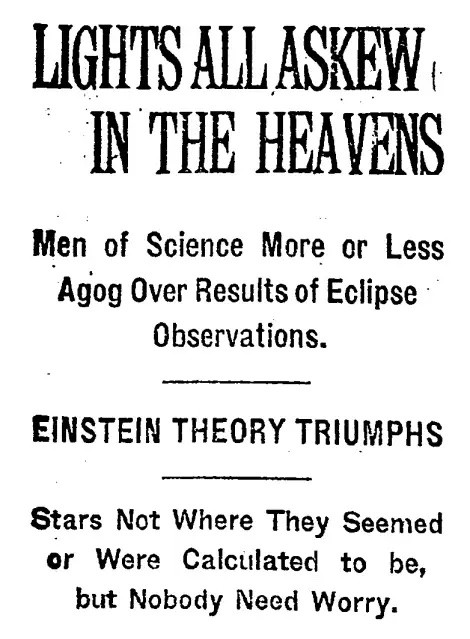

The results of the expedition not only appeared in scientific publications but also found their way into general press coverage. The London Times included an article on the subject on 7 November 1919 immediately after the findings were announced. It also featured in The New York Times on 10 November 1919.

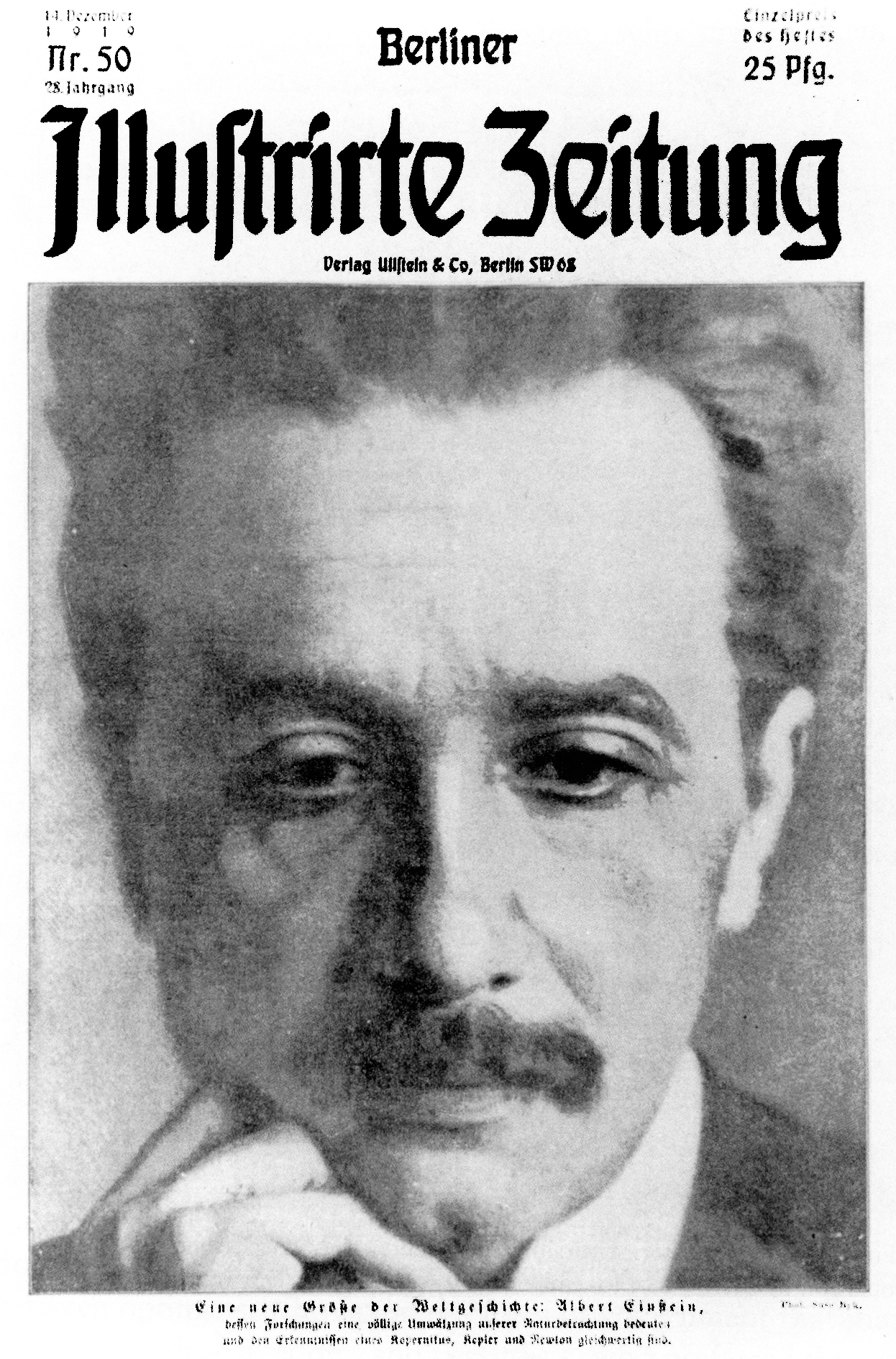

More than a month passed before this scientific breakthrough was acknowledged in the German press as well. On 14 December 1919 the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung featured a picture of Einstein on its front page.

Einstein was now a world-famous physicist, and the fact that his theory had been verified by an Englishman was keenly felt in a Germany that, after its defeat in the First World War, was keen to rehabilitate itself by celebrating other achievements, even as nationalist tendencies continued to run deep. There was one person who knew how to use this situation to his advantage: Erwin Finlay FreundlichErwin Finlay Freundlich (1885–1964) was an astrophysicist. In 1910 he became an assistant at the Berlin Observatory. He joined Einstein’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in 1918, becoming its first member of staff. He drew up plans for the Einstein Tower, which was to be the most powerful solar observatory in Europe. He was made director of the Einstein Tower in 1920. He was expelled by the Nazis and became a professor of astronomy in Istanbul. He was offered a professorship at the German University in Prague in 1936 and fled to Holland in 1939. He then took up a post at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he established an astronomy department, together with an observatory. He became Napier Professor of Astronomy in 1951.. He played on the national pride of German industrialists and politicians and used the “Einstein Donation Fund” as a means to secure enough money for the construction of a facility that would make it possible for independent research to be conducted based on the theory of relativity. One of his objectives here was to verify the one prediction of Einstein’s that had not yet been empirically confirmed: the red shift of light.