The Einstein Tower was officially opened on 6 December 1924, at a meeting of the board of trustees of the Einstein FoundationEinstein Foundation: Successor to the Einstein Donation Fund. Board of trustees of the Einstein Donation Fund: Albert Einstein, Gustav Müller (director of the AOP, 1917–21), Erwin Finlay Freundlich and Rudolf Schneider (managing director of the Reich Association of German Industry). In 1921 it was converted into the Einstein Foundation. The board of trustees now also included Hans Ludendorff, the lawyer Ludwig Ruge, and Carl Bosch (director of BASF) as well as two representatives of the Prussian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs and other representatives from the realms of industry, science, and politics.. At this meeting, Erwin Finlay FreundlichErwin Finlay Freundlich (1885–1964) was an astrophysicist. In 1910 he became an assistant at the Berlin Observatory. He joined Einstein’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in 1918, becoming its first member of staff. He drew up plans for the Einstein Tower, which was to be the most powerful solar observatory in Europe. He was made director of the Einstein Tower in 1920. He was expelled by the Nazis and became a professor of astronomy in Istanbul. He was offered a professorship at the German University in Prague in 1936 and fled to Holland in 1939. He then took up a post at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he established an astronomy department, together with an observatory. He became Napier Professor of Astronomy in 1951. gave a report on the research work that had been carried out in the Einstein Tower over the previous two years. He confidently outlined his plan of being able to check the red shift of sunlight using the coelostatA celostat usually consists of two mirrors arranged in a way that a stationary telescope (e.g. a tower telescope) can be used to follow the motion of celestial bodies over the entire course of the day or night. that had finally been installed in the dome and the measuring system in the underground spectrograph room. At that time, the Einstein Tower was Europe’s largest solar research facility. The telescope and the equipment in the laboratory were, for a long time, some of the most powerful installations of their kind in the world.

Original equipment

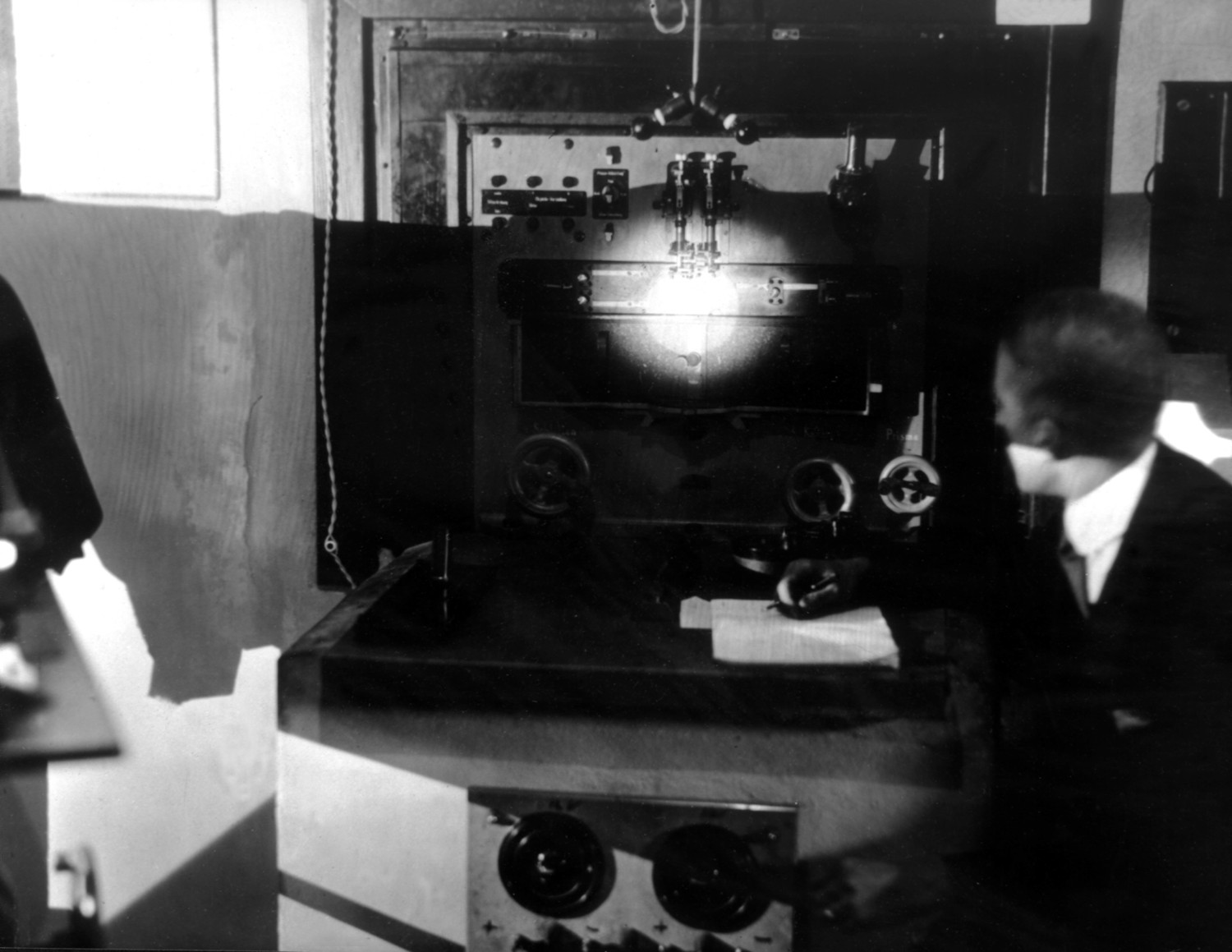

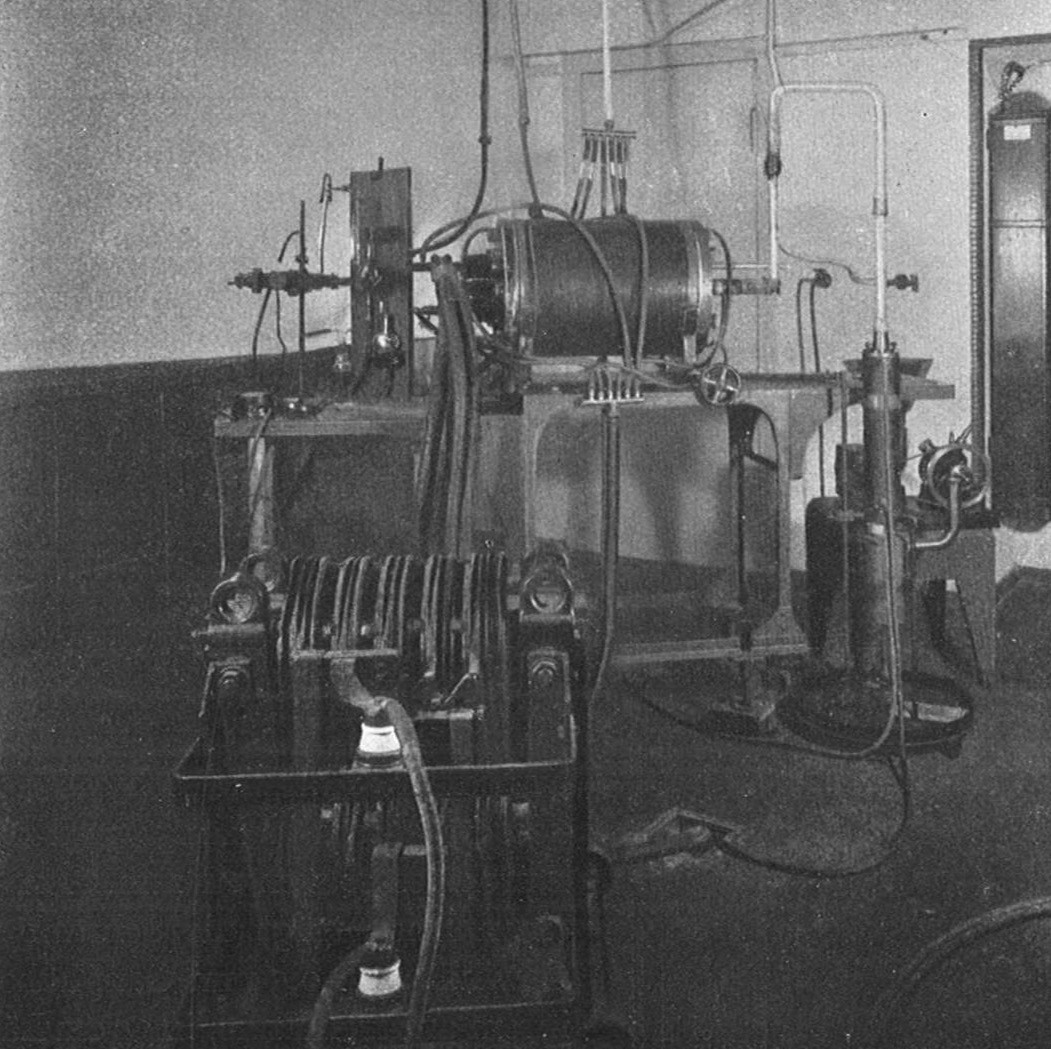

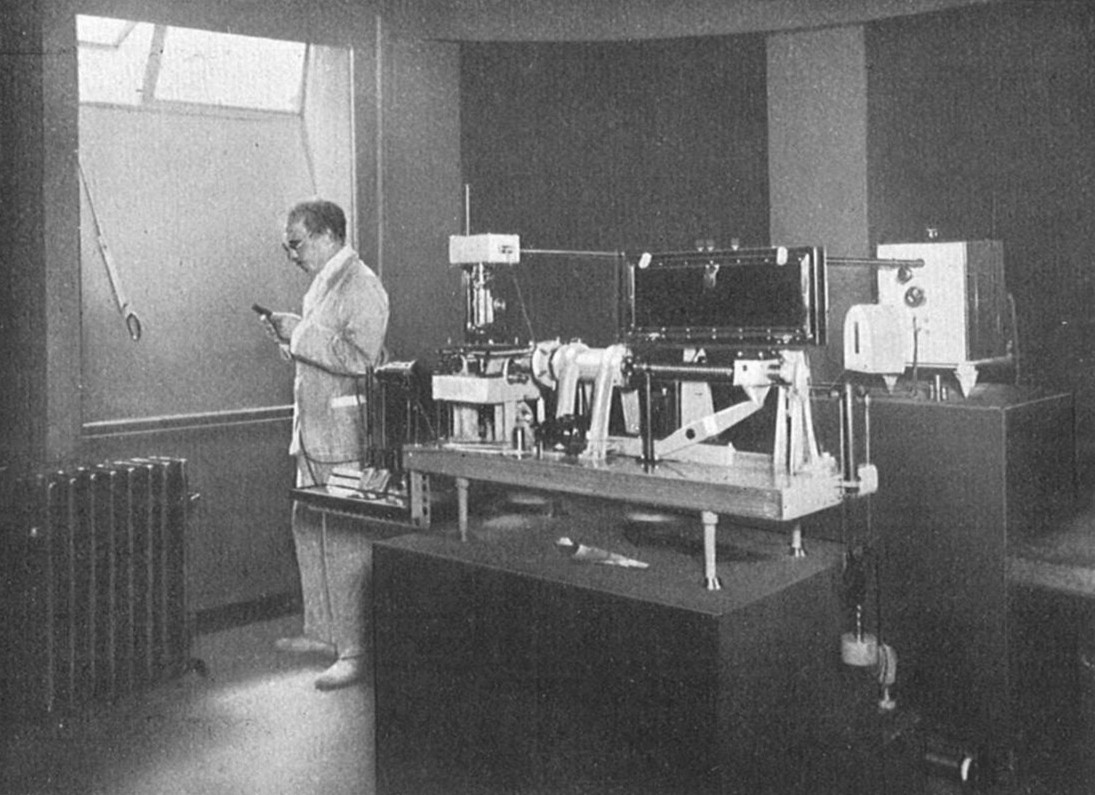

The laboratory contained two different spectrographs: a prism spectrograph with two large quartz prisms and a grating spectrograph with a reflection grating. The original grating spectrograph had a plane grating measuring 12.5 × 9 cm with a total of 100,000 lines. Today’s plane gratings are smaller (4.2 × 3.2 cm and 3.2 × 2.2 cm) and have many more lines (265,000 and 190,000 lines respectively). The sunlight is spectrally dispersed after being diffracted by the grating’s triangular grooves.

Originally, sunlight was compared to two sources of light on Earth: a spectral furnace and an arc lamp. An arc lamp is an electric light source with an arc burning in the air between two graphite electrodes and a capacity of up to 10 kilowatts. The spectral furnace can be heated in a vacuum to a temperature of 3,000°C. It was hoped that temperature and pressure conditions could be generated that would mimic those on the coolest stars and that the light from the furnace and the lamp could be compared with that of the Sun.

Study of the magnetic field of the Sun and the solar corona

EinsteinAlbert Einstein (1879–1955) was one of the most important physicists in the history of science. He began developing the theory of relativity in 1905. In 1914 he joined the Prussian Academy of Sciences and in 1917 became director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, which had been founded for him as a means to support his work. He won the Nobel Prize in 1921 (awarded in 1922). He spent periods teaching and conducting research in the USA. In 1932/33 he went to Princeton, never to return to Germany. He was clearly opposed to Nazi Germany and did not renew his ties with the country, even after 1945. He retired in 1946 and continued his work as professor emeritus at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton. and FreundlichErwin Finlay Freundlich (1885–1964) was an astrophysicist. In 1910 he became an assistant at the Berlin Observatory. He joined Einstein’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in 1918, becoming its first member of staff. He drew up plans for the Einstein Tower, which was to be the most powerful solar observatory in Europe. He was made director of the Einstein Tower in 1920. He was expelled by the Nazis and became a professor of astronomy in Istanbul. He was offered a professorship at the German University in Prague in 1936 and fled to Holland in 1939. He then took up a post at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, where he established an astronomy department, together with an observatory. He became Napier Professor of Astronomy in 1951. were well aware that it would not be easy to prove the relativistic red shift. It quickly became evident wherein the real challenge lay. Although the tower made it possible to detect Einstein’s predicted red shift at the edge of the solar disc, at the centre of the Sun there was a dominant violet shift that countered the red shift. Moreover, these very small shifts were masked by turbulence on the surface of the Sun. As a result, the scientists at the Einstein Tower changed their research focus to concentrate on the outer layers of the Sun and the turbulence occurring there. The study of the Sun’s magnetic field and atmosphere is still a key area of research at the AIPLeibniz Institute for Astrophysics (AIP): Founded in 1992 as the successor of the Central Institute for Astrophysics and renamed Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in 2011. The AIP’s research areas cover solar and stellar physics with a focus on extragalactic astrophysics and solar and stellar physics, with emphasis on stellar and cosmic magnetic fields, star and galaxy formation, and cosmology. The AIP has a share in several telescopes on the Teide volcano in Tenerife and is a partner of the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona. It has also developed astronomical instrumentation for large telescopes such as the Very Large Telescope of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). today.

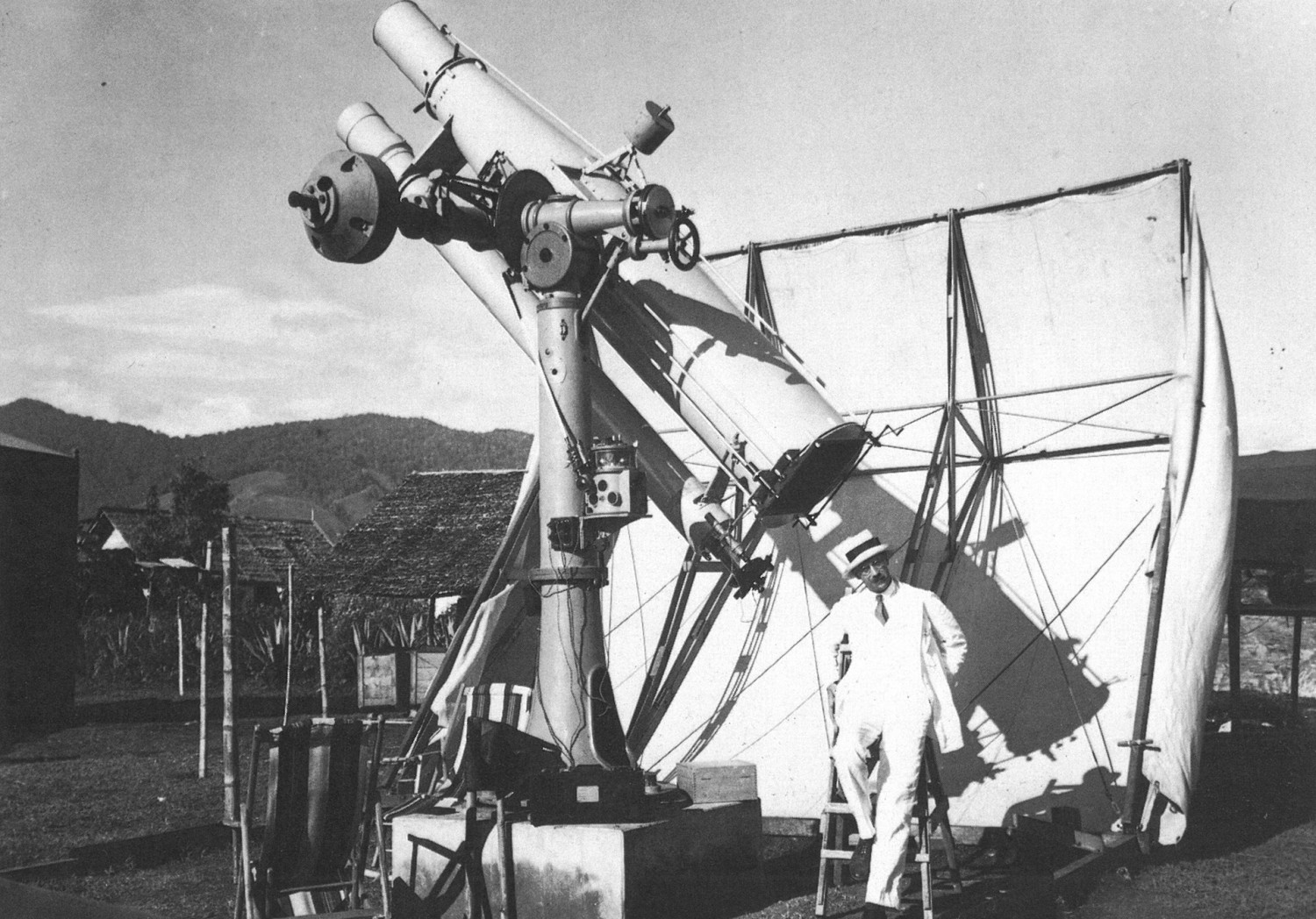

Harald von KlüberHarald von Klüber (1901–1978), astrophysicist, studied with Max Planck and Albert Einstein in Berlin. He joined Freundlich’s team in 1923 and was instrumental in getting the Einstein Tower’s scientific equipment up and running. In 1946 he became director of the solar physics department. In 1948 he joined the Arosa Observatory at ETH Zurich, and in 1949 he took up a position at the Cambridge Observatory in England, becoming assistant director there in 1961. He studied solar corona and made multiple expeditions to view solar eclipses all over the world., one of Freundlich’s early collaborators, developed a means of studying the strength and direction of the Sun’s magnetic fields. Walter GrotrianWalter Grotrian (1890–1954), astrophysicist, started working at the Einstein Tower in 1922 and was appointed professor of astrophysics at Humboldt-Universität in Berlin in 1927. He pioneered research into solar corona and introduced the so-called Grotrian diagrams, which show the energy levels of atoms and are still in common use today. focused on the solar corona. On a 1929 expedition to Sumatra organised with Freundlich to view the solar eclipse, he discovered that the solar corona has a temperature of over 1,000,000°C, a milestone in solar research. Grotrian also constructed a model at the Einstein Tower showing the physical nature of sunspots.

Several expeditions to view solar eclipses set off from the Einstein Tower. The 1922 expedition to the Christmas Islands in Indonesia was unsuccessful because of bad weather. With support from Grotrian and Klüber, Freundlich planned further expeditions to Sumatra (Benkoelen in 1926 and Takengon in 1929) to investigate various research questions, including the relativistic deflection of light, and to verify what Arthur EddingtonArthur S. Eddington (1882–1944), astrophysicist, was an early supporter of Einstein’s theory of relativity. He became director of the Cambridge Observatory in 1914. In 1923 he published one of the first textbooks on the theory of relativity. Since Eddington seasoned many of his books with vivid examples and humorous anecdotes, his works on the philosophy of science were also read outside the scientific community. had ascertained on his 1919 expedition to Príncipe and Brazil.

Einstein’s and Freundlich’s ouster at the hands of the Nazis

In the 1920s, the Einstein Tower offered conditions for conducting research that were rare, if not unique, in Europe. This was not only a matter of the funding available and the tower’s technical amenities but also had to do with the extensive network of astrophysicists around the world that Freundlich was in contact with. On 1 October 1931, as stipulated in its statutes, the Einstein Tower, which had previously been set up as a private foundation, passed into the hands of the state. Although there had been long-term conflict between the two scientists, Freundlich still managed to get Einstein (who had actually broken off contact with him in 1925) to give his support to the tower’s autonomy, which was conclusively terminated when the Nazis came to power. The AOPAstrophysical Observatory Potsdam (AOP): Founded in 1874 to conduct systematic research into the chemical composition and physical states of celestial bodies using the newly discovered method of spectral analysis. The main building on the Telegrafenberg hill in Potsdam was completed in 1879. After the Second World War, it was taken over by the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin and turned into the Central Institute for Astrophysics of the GDR in 1969. Predecessor of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP). director and Nazi sympathiser Hans LudendorffHans Ludendorff (1873–1941) was an astrophysicist. He joined the Astrophysical Observatory Potsdam (AOP) in 1898 and became its director in 1921. He was an opponent of Freundlich, who seemed to him to be too high-handed in his work at the Einstein Institute, which at the time was still separate from the AOP. In 1933 Ludendorff, who was a Nazi sympathiser, began cutting ties with the international scientific network that had been built by Freundlich in particular and focused instead on the Nazi research agenda, investigating ways of predicting disruptions to military communications caused by solar activity. knew how to profit from the new power dynamics. In April 1933, the Einstein Tower was renamed the “Institute for Solar Physics” and fully incorporated into the structure of the AOP. Ludendorff and the Nazis in the Ministry of Culture forced out Freundlich, whereupon he accepted the offer of a professorship at the university in Istanbul. In 1932 Einstein had gone to teach at Princeton University in the USA, never to return: he openly criticised German fascism at a time when most countries were still cooperating with Nazi Germany.

Prediction of radio interference

Solar physics was regarded as “crucial” for the Nazi war effort to enable them to predict radio interference caused by solar activity. Although there were discussions in the spring of 1941 about tearing down the Einstein Tower and rebuilding it in a new form, the research work continued nonetheless in Mendelsohn’s building, which was often still referred to as the Einstein Tower in official Nazi correspondence, even if the name was put in quotation marks.

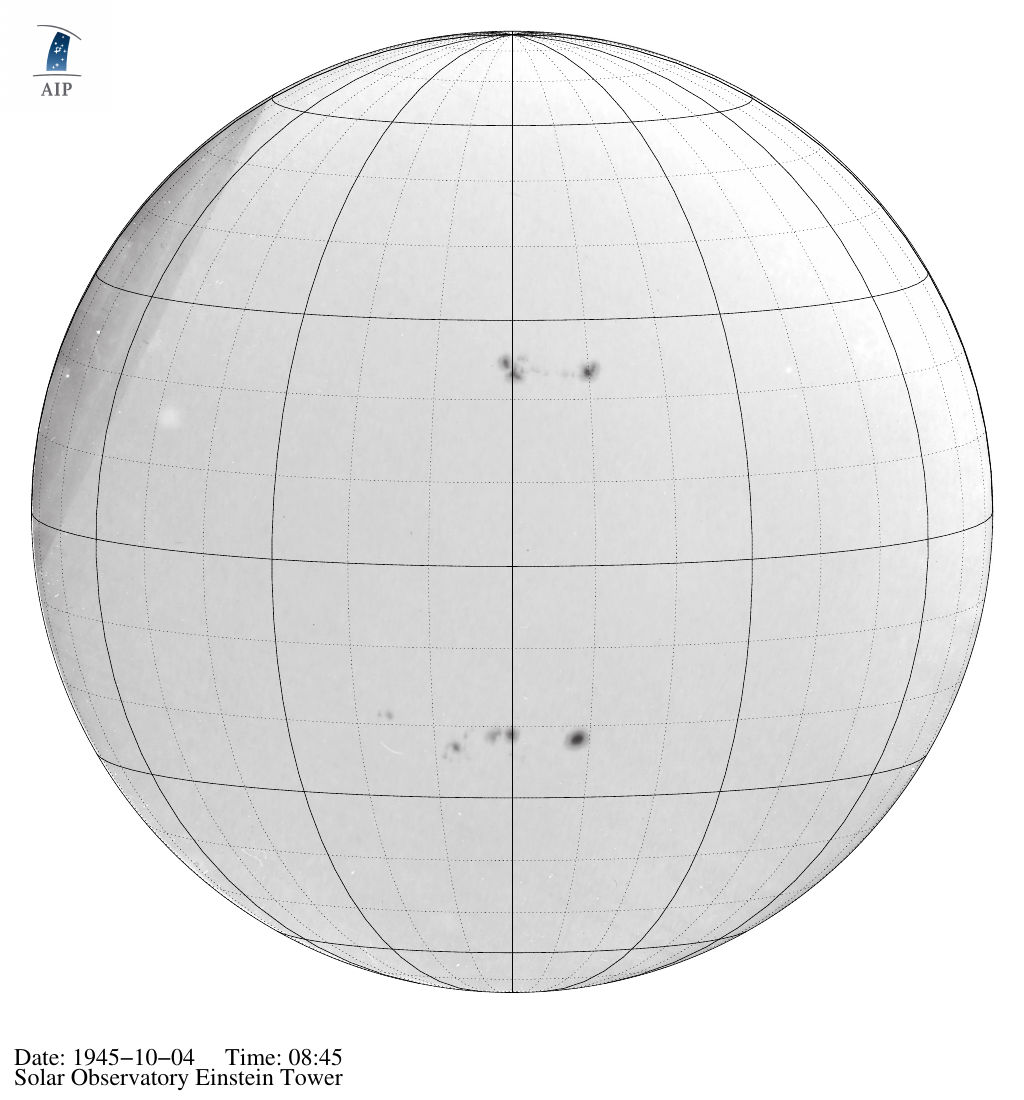

Historic sky

Between 1943 and the mid-1980s, some 3,000 full-image photographs of the solar disc and shots of the starry sky were recorded on glass plates on which sunspots and solar faculae (areas of increased brightness and temperature) could be identified. The archive of these glass plates is still stored in the Einstein Tower and can be accessed digitally on the websites of the AIP.